Recently, my daughter and I were skiing at Beaver Creek. We happened to share a chairlift with an instructor on our first ride up. We are both still novices, and from the lift the mountain looked forgiving—clear skies, groomed snow, wide runs. Everything appeared manageable. I told Alina it looked like a good day for two people who had more confidence than ability to be out on the mountain.

As we rode up, the instructor pointed out things we had missed. Snowfall had been limited, leaving fewer runs open and pushing more skiers onto the same trails. The instructor cautiously detailed how traffic was heavier than usual, leading to major backups and severe collisions at key choke points. In some areas, limited snowfall left a thin layer of snow that concealed patches of ice beneath. Conditions appeared benign, but injuries mounted—likely the result of the dangerous combination of widespread overconfidence coupled with these more subtle hazards. None of this was obvious from me and Alina hovering above, but all of it matters once you are on the mountain. What struck me was how misleading my initial read had been. From a distance, conditions looked calm. Only after listening more carefully did it become clear that the margin for error was narrower than it appeared.

That experience captures something that feels true about fixed income markets today.

Basic optics would lead most to conclude that conditions are benign. Prices are stable, credit spreads are near historically tight levels, refinancing looks easy for most issuers, and valuations assume the road ahead stays smooth. Markets are not broadly pricing stress. For many investors, that calm feels reassuring.

But strong valuations do not mean low risk. As on the mountain, smooth surfaces can conceal hazards that only reveal themselves once you are in motion, and overconfidence born of seemingly benign conditions can itself create incremental risk. In fixed income, the costliest mistakes tend to occur not when conditions look difficult, but when they look easy.

At Harris | Oakmark, price is risk

When markets are calm and prices are high, it is tempting to believe that risk has diminished. Securities trade smoothly. Refinancing looks easy. Credit spreads sit near their tightest levels. Very little appears wrong.

That is usually when we slow down.

In environments like this, opportunity tends to be selective rather than widespread. With spreads this tight, forward returns are likely to come primarily from income if conditions remain constructive, not from a repricing of risk. That is not a bad outcome. It simply means investors are being paid to clip coupons, not to be heroes.

At Harris | Oakmark, we remind ourselves that price is risk. A security purchased at the right price can absorb bad news. The same security purchased at the wrong price cannot. Smooth pricing can create a false sense of safety when valuations assume favorable outcomes. The danger is not volatility. It is paying too much for certainty.

This is why we focus on long term fundamentals. We focus on how an issuer’s leverage is likely to evolve over time and its ability to meet interest and other fixed-charge obligations based on our expectations for profitability. Importantly, we also focus on downside risk, as credit is ultimately priced on the probability of default or impairment. If our assumptions prove wrong due to company-specific factors or broader economic shifts, we assess an issuer’s ability to meet its obligations even in periods of stress—supported by sufficient asset coverage in the event of liquidity pressure, and by cash flows and capital structures that are flexible and resilient. Those downside risks do not disappear because markets feel comfortable.

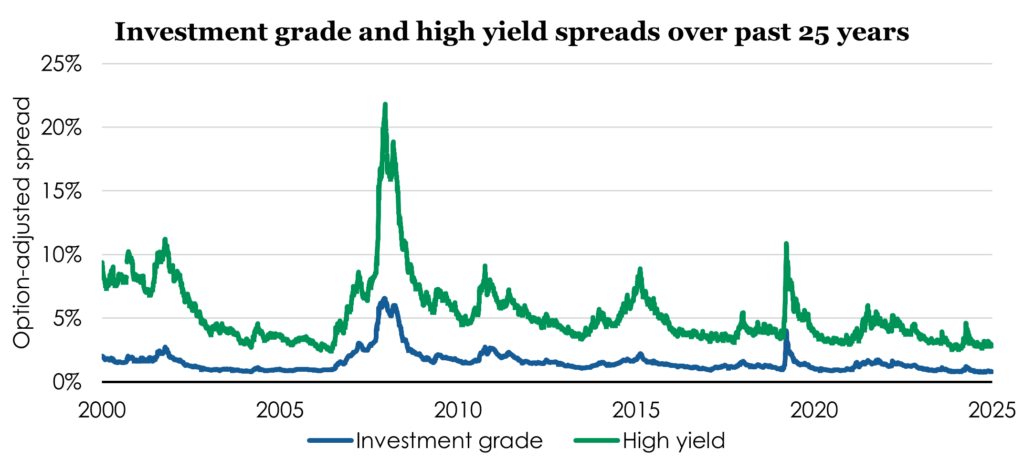

That distinction matters today. As of year-end 2025, investment-grade corporate bonds yielded roughly 4.8 percent with spreads near 80 basis points over U.S. Treasuries. High-yield bonds yielded about 6.5 percent with spreads near 290 basis points. Compensation for taking on corporate default risk sits near the tight end of historical ranges, even as issuer leverage and other key credit metrics have begun to soften modestly. Prices imply confidence, but they leave little room for disappointment.

Data source: Ice Data Indices, LLC, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, investment grade: ICE BofA US Corporate Index, high yield: ICE BofA US High Yield Index, as of 12/31/25.

It is also worth noting what markets appear comfortable overlooking. Geopolitical tensions have escalated across multiple regions, touching major energy producers, trade routes, and global political stability. We do not attempt to predict how these situations will resolve. But it is difficult to argue that they are meaningfully reflected in credit pricing today.

Although it feels like much longer, less than a year ago policy headlines around tariffs—ultimately more negotiating posture than a willingness to disrupt the global economy with 100% plus tariffs—were enough to push high-yield spreads roughly 60 percent wider in a short period, with investment-grade spreads widening by approximately 55 percent. Today, arguably more consequential developments are generating little reaction at all. That contrast is worth keeping in mind.

We are also mindful of the growing role private credit plays in today’s market. In many cases, assets that might have repriced more quickly in public markets during periods of stress are now held in structures with different liquidity, valuation, and reporting dynamics. That does not make these investments inherently risky. However, it can slow the feedback loop that market pricing typically provides and, in doing so, delay the recognition of underlying issues. While private credit is not yet systemically important, in my view (mainly, because of size), it is increasingly intertwined with many of the most important issuers in major fixed income benchmarks. When feedback is muted, price discovery tends to arrive later—and more abruptly.

We are similarly attentive to conditions among lower and middle-income consumers. Early signs of stress, including higher delinquencies and slower repayment behavior, emerged in the second half of last year. These trends are not yet decisive and more recently have actually decelerated, but they warrant attention in a market that appears to be pricing in very little risk across several fixed income asset classes.

Taken together, these observations do not argue for wholesale caution; they argue for selectivity. Today, we are finding value in select areas of the non-agency securitization market and are increasingly spending time evaluating opportunities in corporate credit to potentially add exposure in higher-quality but recently pressured sectors such as chemicals, technology, healthcare, and others that we have been historically underweight versus our peers and broader benchmarks.

Importantly, some of the repricing in these areas is warranted, as fundamentals have deteriorated. Where we look to add exposure is where the market has overreacted—pushing prices too low or failing to give sufficient credit to companies with the ability to recover over time. Within these sectors, there are also issuers where the risk of further fundamental erosion is appropriately reflected in valuations, which makes careful security selection essential. Our focus is on identifying companies that have been unduly penalized by broad sector sentiment rather than by their own fundamentals.

Risk is inherent in lending. The relevant question is whether we are being adequately compensated for taking it.

That discipline also preserves flexibility. By not forcing investments when valuations are full, we maintain the ability to act when prices move faster than fundamentals. This is often most valuable when it feels least necessary. We recognize that this approach is not always comfortable. In calm markets, discipline can feel like inactivity. We accept that discomfort. We would rather risk looking early than be forced to act only after prices adjust.

Preparing for when conditions change

Calm conditions do not eliminate cycles, they postpone the reminder that cycles exist. We were reminded of this earlier in 2025. From April through June, tariff-related headlines triggered a rapid shift in sentiment. Spreads widened, prices adjusted, and liquidity thinned. What stood out was how little fundamentals had changed. Balance sheets remained intact. Cash flows were stable. Structural protections held. Prices changed far more than economic reality.

Because Harris | Oakmark entered that period conservatively positioned, we were not forced to respond defensively. Valuations earlier in the year had not justified leaning in. When prices dislocated and sentiment shifted, we were able to act. Over the first five months of the year, we added roughly twelve points of credit risk, deploying capital selectively where prices moved more than fundamentals.

That episode reinforced a simple lesson. Preparedness is part of discipline. Waiting is not inactivity. It is positioning. Periods of stress rarely announce themselves. They arrive quickly and are amplified by investor psychology. When they do, the window to act is often brief. Being ready matters more than being early.

Today, valuations again imply confidence, and opportunity is narrower. We are conservatively positioned, as we were at the beginning of last year. That posture is intentional. We do not try to predict when the next period of stress will arrive. Markets have a long history of surprising investors. What we can control is readiness, the ability to act when emotions detach from fundamentals, and the patience to wait when they do not.

The mountain does not announce when conditions change. A trail that looks easy from the lift can demand more attention halfway down. Fixed income investing works the same way. By staying disciplined when valuations are mostly full and prepared to act when prices dislocate, at Harris | Oakmark, we seek to manage risk deliberately and deploy capital when opportunity is real, not simply when it looks comfortable.

OPINION PIECE. PLEASE SEE ENDNOTES FOR IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES.

Important Disclosures

This material is not intended to be a recommendation or investment advice, does not constitute a solicitation to buy, sell or hold a security or an investment strategy, and is not provided in a fiduciary capacity. The information provided does not take into account the specific objectives or circumstances of any particular investor, or suggest any specific course of action. Investment decisions should be made based on an investor’s objectives and circumstances and in consultation with his or her financial professionals.

The information, data, analyses, and opinions presented herein (including current investment themes, the portfolio managers’ research and investment process, and portfolio characteristics) are for informational purposes only and represent the investments and views of the portfolio managers and Harris Associates L.P. as of the date written and are subject to change and may change based on market and other conditions and without notice. This content is not a recommendation of or an offer to buy or sell a security and is not warranted to be correct, complete or accurate.

Certain comments herein are based on current expectations and are considered “forward-looking statements.” These forward-looking statements reflect assumptions and analyses made by the portfolio managers and Harris Associates L.P. based on their experience and perception of historical trends, current conditions, expected future developments, and other factors they believe are relevant. Actual future results are subject to a number of investment and other risks and may prove to be different from expectations. Readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on the forward-looking statements.

Yield is the annual rate of return of an investment paid in dividends or interest, expressed as a percentage. A snapshot of a fund’s interest and dividend income, yield is expressed as a percentage of a fund’s net asset value, is based on income earned over a certain time period and is annualized, or projected, for the coming year.

Investing involves risk; principal loss is possible. There is no guarantee the Fund’s investment objective will be achieved.

Fixed income risks include interest-rate and credit risk. Typically, when interest rates rise, there is a corresponding decline in bond values. Credit risk refers to the possibility that the bond issuer will not be able to make principal and interest payments. Bond values fluctuate in price so the value of your investment can go down depending on market conditions.

The Oakmark Bond Fund invests primarily in a diversified portfolio of bonds and other fixed-income securities. These include, but are not limited to, investment grade corporate bonds; U.S. or non-U.S.-government and government-related obligations (such as, U.S. treasury securities); below investment-grade corporate bonds; agency mortgage backed-securities; commercial mortgage-and asset-backed securities; senior loans (such as, leveraged loans, bank loans, covenant lite loans, and/or floating rate loans); assignments; restricted securities (e.g., Rule 144A securities); and other fixed and floating rate instruments. The Fund may invest up to 20% of its assets in equity securities, such as common stocks and preferred stocks. The Fund may also hold cash or short-term debt securities from time to time and for temporary defensive purposes.

Under normal market conditions, the Fund invests at least 25% of its assets in investment-grade fixed-income securities and may invest up to 35% of its assets in below investment-grade fixed-income securities (commonly known as “high-yield” or “junk bonds”).

These and other risk considerations such are described in detail in the Fund’s prospectus.

All information provided is as of 12/31/2025 unless otherwise specified.