Oakmark Bond Fund – Institutional Class

Average Annual Total Returns 12/31/22

Since Inception 06/10/20 -2.32%

1-year -11.12%

3-month 2.22%

Gross Expense Ratio: 0.89%

Net Expense Ratio: 0.52%

Expense ratios are as of the Fund’s most recent prospectus dated January 28, 2022, as amended August 1, 2022 and October 1, 2022; actual expenses may vary.

The Fund’s Adviser has contractually undertaken to waive and/or reimburse certain fees and expenses so that the total annual operating expenses of each class are limited to 0.74%, 0.54%, 0.52% and 0.44% of average net assets, respectively. Each of these undertakings lasts until 1/27/2023 and may only be modified by mutual agreement of the parties.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. The performance data quoted represents past performance. Current performance may be lower or higher than the performance data quoted. The investment return and principal value vary so that an investor’s shares when redeemed may be worth more or less than the original cost. To obtain the most recent month-end performance data, view it here.

Questions from the Fixed Income Desk: A Perspective for 2023

The most well-received commentary last year was our fourth-quarter memo, in which we responded to our clients’ three most frequently asked questions heading into the new year, instead of providing our standard market commentary. Given the positive feedback, we decided to repeat this format, especially as it seems even more pressing as we head into an even more complex and uncertain year ahead. To be clear, our responses don’t aim to be definitive answers, but are more of a map for informed market navigation. This map is not an “X marks the spot” treasure map so much as a seafaring map that highlights preferred paths and potential obstructions to help investors cross increasingly turbulent market waters. [For those who want an even deeper analysis of the structural changes within the fixed income markets, we recommend Q1’22 and Q3 ‘22 commentaries along with Howard Marks’ latest memo, aptly named “Sea Change.”] Like last year, we’ve clearly marked the client question below, so feel free to hop around to the ones you find most interesting.

The three most frequently asked questions to the Oakmark fixed income desk over the past month:

- Is the war on inflation over or is the battle between prices and central banks still undecided?

- What is the Fed’s playbook in 2023, and how does it compare to current market expectations?

- Will there be a U.S. recession next year, and if so, how bad will it be?

1. Is the war on inflation over, or is the battle between prices and central banks still undecided?

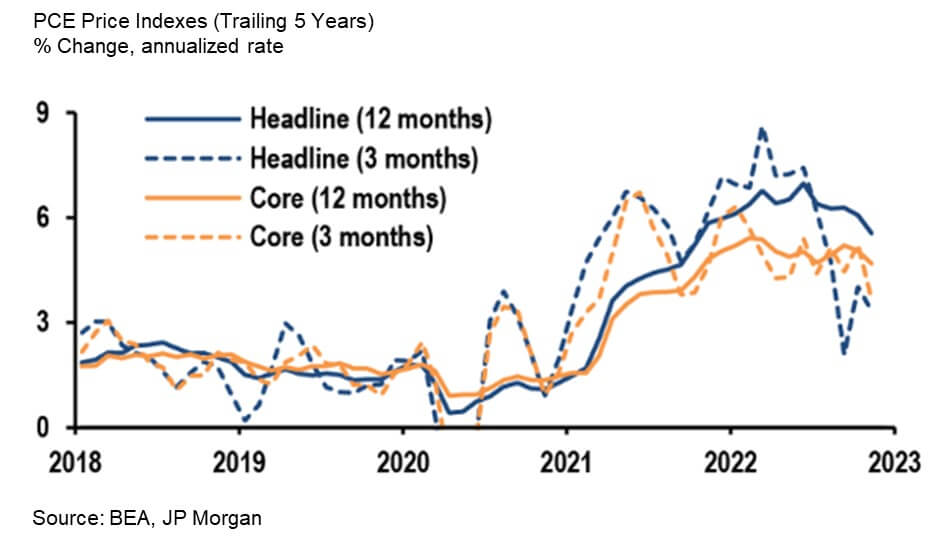

First, to address the basic question, the inflation fight certainly isn’t over, but recent price indexes show momentum building in favor of the Fed. Before we get into the details of this answer, we want to emphasize that the Fed’s actions in 2023 alone will not be enough to determine if this war is over. Many analysts have recently—and in our view incorrectly—reduced the main signal for the outcome of the battle to be whether or not the Fed is able to cut rates in 2023 (the market is currently pricing in cuts by mid-year, which implies that rate easing is a forgone conclusion). The problem with this reductionist framework is that it ignores the driver of the rate cuts. If you want to understand the market’s definition of success in the Fed’s war against inflation, the most important question to ask isn’t if rate cuts continue over a specific time frame, but why the cuts occur. We believe that one of the most critical determinants for a soft-ish landing (i.e., a flat to shallow recession) within domestic markets in 2023 is whether inflation pressures will ease organically so that the Fed feels free to back away from its restrictive policy and begin the easing cycle. We italicize the words organically and free to distinguish this situation from one in which inflation pressures instead are pushed lower as a reaction to a collapse in real economic demand, which would then force the Federal Reserve to reverse its restrictive policy. We stressed this point in a recent interview with The Wall Street Journal (“A crucial question hanging over the market is what exactly will prompt the Fed to cut rates”): potential rate declines in 2023 on their own don’t tell us anything about the state of markets or about the success of the Fed’s mandate. Market participants must instead understand why the Fed is cutting rates to glean any meaningful takeaways for market valuations.

So, let’s examine the right framework of what it means to win the inflation war for the Fed and the markets. What is the likelihood that inflation can continue to come down organically without a major reset in real economic demand and unemployment?

We believe that it is more likely that inflation will decrease organically than most prevailing market narratives suggest. Just as consensus views at the beginning of 2022 were too heavily weighted to “transitory” and “healthy sustained real growth” narratives, today at the beginning of 2023, the consensus views are too heavily weighted to “sticky structural inflation” and “major demand destruction.” Yet, everywhere we look, the inflationary shocks that took place over the past 36 months are unwinding. Goods prices led the way first as U.S. consumers shifted their preference from goods to services, and freight costs normalized. In 2023, the price of goods will likely continue to decelerate as consumption moderates further, supply chains are fully frictionless, and high inventory levels are significantly discounted and subsequently cleared. In fact, we believe the rate of core goods price inflation will not only continue to decelerate, but eventually prices are to see absolute declines as we move further into the year. We also see that the cost of rents will become more manageable. New rents in top markets are already slowing significantly, and vacancy rates are increasing. It will take several quarters for this category to normalize because of the time lag associated with existing contracts, but we expect progress to be very evident by the second half of 2023. Although the travel and hospitality industries will likely be more resilient overall than the price of goods or rents, we believe this sector will also experience a material deceleration in price growth as consumers finally work through their pent-up Covid-19-related demand and deplete their savings. Finally, we can’t forget about the long-term structural headwinds that will persist in the background, including the ongoing shift to service economies in developed markets, increasing price transparency, globalization of the labor force, and well-anchored long-term inflation expectations.

We see plenty of evidence that inflation could come down naturally next year as part of a slowing or slightly contracting economy instead of due to a major recession. However, saying an outcome is underappreciated is not committing to it being realized. We acknowledge there are significant risks to our forecast. Ignoring the collapse of the demand side for now (which we cover in question #3), the most notable risk to organically lowered inflation is an upward pressure on wages. Even with decreased corporate profits and declining economic indicators, the labor market is still stubbornly tight due to a constrained labor pool supply and a large number of job openings. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell appears keenly aware that the labor market is the last major fire he needs to control before he can comfortably believe that inflation will approach his 2% target. However, it is difficult to predict when or by how much the labor market will begin to respond to the Fed’s unprecedented tightening efforts implemented in 2022. All that is clear today is that the unemployment rate in the U.S. remains stubbornly strong and should weaken at some point in 2023 as aggregate demand recedes. But is the Fed’s current forecasted terminal rate of ~5.0% substantial enough to weaken employment and fully extinguish the upward wage pressures, and for how long should the Fed maintain such restrictive rates to ensure inflation doesn’t flare up across all major categories again? That’s a perfect segue to our next most asked question from clients.

2. What is the Fed playbook in 2023, and how does it compare to current market expectations?

Even if we take the contrarian view that inflationary pressures could abate next year alongside a smoothly descending economy, the Fed’s actions will still determine the ultimate success of the landing. For Powell, there are two critical maneuvers to landing this jumbo jet of an economy: first, he must reduce the speed of price growth to somewhere near his 2% mandate. If not, he risks future inflationary flare-ups. Of course, the Fed has one main throttle for slowing price growth that it can control today: interest rates. Theoretically, there is a rate level that the Fed believes should be restrictive enough (and, thus, the peak level) to ensure inflation is placed on a comfortable glide path downward to its stated 2% objective, which is referred to as the “terminal rate.” Today, both the Fed and markets believe the terminal rate is about 5%. However, you can’t keep a plane throttled back indefinitely on descent or your jet engine will slow too much and nosedive into the runway, slamming our economy straight into the ground. This brings us to the second maneuver for slowing price growth: knowing when to let off the throttle, bring rates back from the 5% level and begin to ease into a safe landing for the economy. This final maneuver will be by far the trickiest, and we believe it holds the biggest risks to outcomes of the next year.

In our analysis, the 5% terminal rate that is priced in by markets today is indeed the correct level. That means we believe the Fed will enact between 50 to 75 basis points of hikes over its next few meetings to achieve a terminal rate of ~5%. However, we disagree with the market, which is currently pricing in rate cuts already starting in the third quarter of 2023 and implying rate levels ending the year a significant ~75 basis points lower to ~4.25%. For that to be accomplished, there would need to be a much stronger deterioration in the labor market and consumer spending than we currently expect. (We expand on our analysis of this issue in question #3.) Instead, we think growth and unemployment will both reverse more gradually and that the Fed will more likely pivot to a dovish approach mid-year, but it will do so through signaling, not action. We expect in the second or third quarter to read commentary that implies Chairman Powell is done with hikes and is shifting away from a focus on inflationary risks and toward the risks of a deteriorating growth outlook. In this scenario, rate cuts are more likely to begin late in the fourth quarter after labor markets have sufficiently reset and the risks of a re-inflationary episode are completely stamped out. Although some might interpret our playbook as bearish for most assets, we don’t see it that way whatsoever. We believe that rates will be higher for longer than the consensus estimates—not in independence, but as a result, of our assumption of a fairly smooth deceleration of the economy. (Remember the focus isn’t on if we are getting cuts, but why.) However, some possible scenarios do concern us. The primary one is if the Fed stays too restrictive for too long, regardless of how quickly the economy decelerates. It’s possible to imagine a scenario in the first half of the year in which synchronous global restrictive monetary policy is compounded by an escalation of exogenous events, such as China’s policies, the war in Ukraine, Covid-19 spikes, etc., and then both real demand and the labor market in the U.S. could deteriorate much more quickly than we expect. Will the Fed be willing to pivot to a more dovish stance if the Consumer Price Index remains stuck in the 3.5-4.5% range? Remember: Fed governors don’t get criticized for cyclical recessions, but they do for losing control of inflation (especially when they are partially responsible for creating the problem in the first place). If we are wrong and the economic picture is much worse in the first half of the year, Fed governors may be incentivized to keep the terminal rate high to ensure they don’t end up in the history books, even if that decision puts their economic jumbo jet in a nosedive. Although we do not expect a nosedive and economic crash, it is always prudent to build a proper framework for a range of outcomes, which leads us to our third most popular client question.

3. Will there be a U.S. recession in 2023, and if so, how bad will it be?

Since we participated in our first 2023 outlook event in November, we have consistently asserted that the U.S. economy will most likely experience somewhere between a no-growth to a shallow contractionary scenario for 2023. So, the short answers to question 3 are “yes” and “not very,” respectively. However, we feel compelled to add a longer disclaimer—one that we have given extensively and frequently over the past year, and one that is always worth repeating. The range of outcomes has widened considerably in this new, higher inflation, higher interest rate regime. We are acutely aware of the uncertainty within any macro-economic forecasts over any meaningful timeframe and even more so given today’s particular backdrop. This also explains why you can find such a diverse and extreme set of market opinions for the upcoming year.

Today’s market backdrop is especially complex due to the sheer number of critical variables moving at the same time in different directions and with different influences. Even though investors in 2022 had to deal with rapidly rising inflation and an ultra-hawkish Fed, those forces were at least mitigated by strong real underlying demand. In 2023, investors need to navigate a weaker demand backdrop but then calibrate for a Fed policy that will eventually signal a less restrictive stance as disinflation eventually gathers momentum. What we know today—and why our base case is a recessionary (albeit shallow) period for next year—is that a robust set of reliable signals point clearly to an upcoming economic contraction. Yield curve inversion (2-year U.S. Treasury/10-year U.S. Treasury at a -70 basis points inversion and 3 month U.S. Treasury/10 year U.S. Treasury at a -85 basis points inversion) and the U.S. Composite Index of Leading Indicators (which has experienced four straight months of year-over-year declines) have been two of the best predictors of economic recessions and have been flashing red for several months. It’s been hard for us to find any reason, especially in a period with no fiscal or monetary stimuli waiting on the sidelines to play savior, that a contraction won’t indeed manifest. When we said this in New York at the outlook event two months ago, it was slightly controversial, but today a recession view is almost unanimous.

A much more interesting debate at this juncture is the magnitude of the slowdown next year. In the 13 post-World War II contractionary periods, U.S. GDP fell on average by 2.5%, and unemployment rose by 3.5%. As we mentioned before, our base case is a shallow recession; a GDP decline much closer to zero than the above historical average; and an unemployment rate that also underwhelms the normal recession and shifts 1.5-2.5% higher. Although consumers are burning through their savings, households are in relatively good shape, and corporate balance sheets are much more resilient than they were in the lead up to the global financial crisis. As one might expect given the tighter conditions, the labor market is cooling, but it has not collapsed. We have had three nonfarm payroll prints now under 300,000, and employment surveys point to a further slowdown as we come into the new year. Through the first quarter of 2023, we expect the replacement rate will move close to 100,000, and unemployment will finally begin to reverse and move higher at some time in the second quarter, but in a fairly orderly way.

That leaves inflation as the major outstanding imbalance versus prior recessions, but as we addressed in our opening question, we think the market is underestimating the likelihood that prices could decline naturally and without the requirement of a major drop in demand. We certainly recognize that the housing and auto (both used and new) markets are key sector risks to this scenario. However, we believe both categories are appropriately normalizing from their Covid-19 era excesses, and broader damage can be contained if our beliefs on inflation are accurate. Finally, systemic risks to the economy simply aren’t lingering over the markets as they did in other downturns. U.S. banks are exceptionally well capitalized, and credit risk has been underwritten in a far more responsible manner than during the post-global financial crisis era. Of course, bubbles have burst in some speculative asset classes, and although some analysts have characterized the collapse of alt-coins, NFT (non-fungible tokens), SPACs (special purpose acquisition companies) and other nascent investment classes as the first dominos to fall, alluding to much broader risks on the horizon, we do not view these asset classes as systemic or representative. Their very existence was predicated on an exorbitant amount of post-Covid-19 excess liquidity that needed to find a home. Investors should welcome their collapse as a sign the market is finally behaving rationally.

The major risk of a deeper recession is not from a current unraveling of demand under status quo financial conditions. In fact, we think the demand slowdown will be orderly. Rather, as we detailed in question 2, it will more likely be triggered by a Fed that tightens too much or stays tight for too long in the face of an accelerating economic slowdown. If it does appear that the economy is in more trouble than we anticipate, asymmetric incentives may cause the Fed to delay a needed shift to easing (focus on risks to growth and de-emphasize the threat of inflation).

To summarize our thoughts to our clients’ great questions, the U.S. should be capable of avoiding the challenges most often seen in past deep recessions. Just as analysts were too certain that market conditions were only transitory heading into 2022, today they seem to be overlooking the probability that inflation can normalize organically and without requiring a significant demand shock. The foundations of the U.S. economy—households and the banking system—are reasonably healthy, and the labor market is more resilient than in previous recessions. Corporations have cleaned up their balance sheets and extended runways. We believe these strong fundamentals will give the Fed coverage to stay at its terminal rate longer than the consensus expects, and that it can extinguish inflation and prevent future flare-ups. Aside from inflation, the economy is facing no apparent structural issues, and we therefore expect GDP declines to be shallow. A deeper contraction seems unlikely, but we will pay close attention to the Fed’s (un)willingness to pivot to a more dovish strategy if the economy and unemployment situation deteriorate much faster than we expect. We recognize that if the Fed is too stubborn to loosen its policy or if exogenous events become threatening, our shallow recessionary view will need to be revised.

Conclusion

With our outlook in mind, we prefer to move deliberately, but also opportunistically, into 2023. Instead of significant and widespread demand destruction, we expect a shallow recession with tight persisting financial conditions. This would in turn isolate economic pain to the most fragile areas of the economy. That means that the weakest companies that have been staying afloat for the last several years purely on the buoyancy provided by central bank and fiscal liquidity – commonly referred to as “zombie credits” – will indeed finally be forced to restructure this time around. Positive cash flows, visibility in earnings, robust liquidity profiles, and clean maturity runways will significantly outweigh the importance of revenue growth trajectories or leverage profiles when choosing credits in these lower rated segments of fixed income. Expect to see upcoming restructurings of notable companies in major industries, including theaters, autos, travel and leisure, and retail. The common thread across these companies will be widely apparent: high fixed costs, high cash burn, little to no access to capital markets, a lack of monetizable hard assets, and upcoming debt maturities. However, outside of these select companies, there will be plenty of supra-normal returns in this lower rated arena of companies that can endure this upcoming slowdown in demand. Active management and a bottom-up approach to fundamental research will help sort the survivors from the bankruptcies now more than ever. For investors with less risk appetite or those who are geared to a more passive approach, higher quality fixed income should finally offer high enough yields to generate both competitive total returns and strong relative protection (offered by higher recurring income) from losses versus most asset classes

The past year will be remembered for being one of the most challenging years ever for fixed income markets in terms of returns and for sheer unpredictability. The year was marked by an inflationary spike fueled by an impossible concoction of a pandemic, a war, years of easy money policies (both fiscal and monetary) and an incredulous central bank that was slow to react. The market then watched as the Fed was forced to respond with a pace of rate hikes never experienced before. What a year! It was a painful reminder that sell-offs of major magnitudes are rarely anticipated and are impossible to script. One thing is certain, however: bear markets always do eventually come to an end, and in fixed income, the inevitable expiration occurs through the discounting transmission of price (valuation), time, and higher income. We expect 2023 will continue to be volatile and that it is best to be very discerning in certain areas of lower quality credit. However, if our outlook is anywhere near realized, these discounting mechanisms for most of the fixed income universe are close to running their course.

MARKET OUTLOOK POSITIONING

Positioning

During the quarter, we purchased securities in lower rated tiers to pick up credit spread and yield. We expect to remain active across our favorite securities, including names that are pricing in too dramatic of a slowdown, specific preferreds and select areas of structured credit. As far as curve positioning, we continue to pursue three main strategies: 1) extension swaps out the curve in specific corporates to pick up current yield and total return opportunities on our favorite names, 2) steeper trades in U.S. Treasurys moving out of our longest-dated U.S. Treasurys into shorter dated securities in expectation of a steeper curve next year, and 3) U.S. Treasury swaps into securitized AAA paper to lower direct U.S. Treasury exposure on certain parts of the curve and to capture historically wide spread relationships. We also have been pruning specific high-yield leveraged loans and bonds, particularly in the richer BB quality basket, that have met our fair-value targets. As we move into the new year, we are anxious to pick up activity in the primary market, and we expect to be a much livelier player if the new issue supply starts to weigh on spread and if fundamental weakness slows economic growth. As we repeat for the third straight commentary, this is a time to be active. We will continue to look for relative value swaps within capital structures, across peer groups, and across industries as volatility tends to create more dispersion the longer it persists. Given our expectation of a shallow recession, we are also probing the more economically sensitive high-yield segments to find opportunities for high coupon carry and all-in total returns for the Fund. However, this exercise usually requires a level of diligence that is orders of magnitude more time-intensive than a standard inspection of an investment-grade rated security and we will deploy that capital carefully. Regarding duration positioning, we believe that the beginning of the end of rate hikes is just around the corner, and we assume that although the Fed will continue to strike a hawkish tone, investors will monitor inflation and growth data for leading indicators of upcoming Fed action. As the Fed’s hawkish rhetoric diverges from its actual actions, the belly of the curve may become an attractive area to add duration to the Fund because the front end of the curve will remain anchored to a sticky Fed fund terminal rate while the back end of the curve will re-steepen on implied dovish shifts.

Performance

The Oakmark Bond Fund (“Fund”) returned +2.22% in the fourth quarter ending December 31, 2022, and it generated +0.35% of excess returns versus its benchmark, the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index. For the 12 months that ended December 31, the Fund returned -11.12% compared with the benchmark’s -13.01%. Inception-to-date performance was -2.32% through December 31, 2022, generating excess return against the benchmark of +293 basis points, annually.

The Fund’s relative outperformance in the quarter was driven by the Fund’s security selection and asset allocation. Credit selection added +11 basis points of relative performance led by Freddie Mac structured agency credit risk notes 2022-DNA5 M2, Oceaneering International 6% senior unsecured bonds of 2028, and Altria Group Inc. 2.45% senior unsecured bonds of 2032. The Fund’s biggest detractors included Silicon Valley Bank 4.25% perpetual preferred bonds, Ally Financial 4.7% perpetual preferred bonds, and Signature Bank of New York subordinated bonds of 2030. The Fund’s overweight allocation to corporate credit in combination with its underweight allocation to government debt resulted in a positive allocation effect for the quarter, accounting for the majority of the ~ 35 basis points of outperformance compared to the benchmark. The portfolio’s weighting to corporate credit (inclusive of leveraged loans and preferred bonds) averaged 54% over the period while the benchmark averaged ~25% during the fourth quarter. The Fund’s weighting to securitized products remained stable at ~25% versus the benchmark at ~30%, and its weighting to government bonds was 19% versus 45% for the benchmark. The Fund ended the quarter with an overall duration of ~5.0 years, compared to the benchmark’s duration of ~6.2 years, which resulted in a small contribution of ~5 basis points to outperformance during the quarter.

For the calendar year, asset allocation and duration management drove a majority of the outperformance while security selection was a small detractor. Contributors within security selection for the year were driven by Twitter 5.0% senior unsecured bonds of 2030, Ritchie Brothers Auctioneers senior unsecured bonds of 2031, and T-Mobile USA Inc. senior unsecured bonds of 2022, while the biggest detractors included Silicon Valley Bank 4.25% perpetual preferred bonds, Ally Financial 4.7% perpetual preferred bonds, The Southern Company junior subordinated hybrid bonds of 2051, and Peloton Interactive Inc. senior unsecured convertible bonds of 2026.). The Fund’s overweight allocation to corporate securities—corporate bonds (-8.5 basis points), leveraged loans (+8.2 basis points) and equities (+10.3 basis points)—along with its underweight allocation to government debt and securitized product resulted in a positive allocation effect for the year. Overall allocation decisions accounted for ~33 basis points of outperformance versus the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index. The portfolio’s weighting to corporate credit (inclusive of leverage loans and preferred debt) averaged 56% over the period while the benchmark averaged ~25% during 2022. The Fund’s weighting to securitized products averaged ~17% versus the benchmark of ~30% and its weighting to government bonds averaged 24% versus 44% for the benchmark. The Fund ended the quarter with an overall duration of ~5.0 years versus the benchmark of ~6.2 years. The short duration position throughout the year contributed ~251 basis points to outperformance during the quarter.

The securities mentioned above comprise the following percentages of the Oakmark Bond Fund’s total net assets as of 12/31/2022: Ally Financial 4.700% Due 08-15-69 0.7%, Altria Group CC 11/31 2.450% Due 02-04-32 1.1%, STACR 2022-DNA5 M2 10.678% Due 6/25/42 1.2%, Oceaneering CC 11/27 6.000% Due 02-01-28 0.5%, Peloton Interactive 0.000% Due 2/15/26 0%, Ritchie Brothers Auctioneers senior unsecured bonds of 2031 0%, Signature Bank QC 10/25 4.000% Due 10-15-30 1.0%, SVB Financial QC 11/26 4.250% Due 02-15-69 0.9%, Southern Co CB 06/26 3.750% Due 09-15-51 0.9%, T-Mobile CC 03/22 4.000% Due 4/15/22 0%, and Twitter CC 12/29 144A 5.000% Due 3/1/30 0%. Portfolio holdings are subject to change without notice and are not intended as recommendations of individual stocks.

Access the full list of holdings for the Oakmark Bond Fund as of the most recent quarter-end.

The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index is a broad-based benchmark that measures the investment grade, U.S. dollar-denominated, fixed-rate taxable bond market. The index includes Treasurys, government-related and corporate securities, mortgage-backed securities (agency fixed-rate and hybrid ARM pass-throughs), asset-backed securities and commercial mortgage-backed securities (agency and non-agency). This index is unmanaged and investors cannot invest directly in this index.

The Oakmark Bond Fund invests primarily in a diversified portfolio of bonds and other fixed-income securities. These include, but are not limited to, investment grade corporate bonds; U.S. or non-U.S.-government and government-related obligations (such as, U.S. Treasury securities); below investment-grade corporate bonds; agency mortgage backed-securities; commercial mortgage- and asset-backed securities; senior loans (such as, leveraged loans, bank loans, covenant lite loans, and/or floating rate loans); assignments; restricted securities (e.g., Rule 144A securities); and other fixed and floating rate instruments. The Fund may invest up to 20% of its assets in equity securities, such as common stocks and preferred stocks. The Fund may also hold cash or short-term debt securities from time to time and for temporary defensive purposes.

New Fund Risk: The Fund is recently established and has limited operating history. The Fund may not be successful in implementing its investment strategy.

Under normal market conditions, the Fund invests at least 25% of its assets in investment-grade fixed-income securities and may invest up to 35% of its assets in below investment-grade fixed-income securities (commonly known as “high-yield” or “junk bonds”).

Fixed income risks include interest-rate and credit risk. Typically, when interest rates rise, there is a corresponding decline in bond values. Credit risk refers to the possibility that the bond issuer will not be able to make principal and interest payments.

Bond values fluctuate in price so the value of your investment can go down depending on market conditions.

The information, data, analyses, and opinions presented herein (including current investment themes, the portfolio managers’ research and investment process, and portfolio characteristics) are for informational purposes only and represent the investments and views of the portfolio managers and Harris Associates L.P. as of the date written and are subject to change and may change based on market and other conditions and without notice. This content is not a recommendation of or an offer to buy or sell a security and is not warranted to be correct, complete or accurate.

Certain comments herein are based on current expectations and are considered “forward-looking statements”. These forward looking statements reflect assumptions and analyses made by the portfolio managers and Harris Associates L.P. based on their experience and perception of historical trends, current conditions, expected future developments, and other factors they believe are relevant. Actual future results are subject to a number of investment and other risks and may prove to be different from expectations. Readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on the forward-looking statements.

All information provided is as of 12/31/2022 unless otherwise specified.